Sleep Paralysis: Conscious Yet Frozen

You are in your bed after a long day, about to fall asleep. You finish reading your book, scrolling on your phone, sending an email, and hit the hay. Then, you wake up the next day in your bed. You might have been dreaming about frolicking in a field, cleaning your house (I hope not), going on vacation, or a variety of other things. But… you wake up in your bed. Not in a different country, not in a different area outside of your home, not even in a different room in your home. You wake up in the exact same place where you went to sleep: your bed. How is this possible?

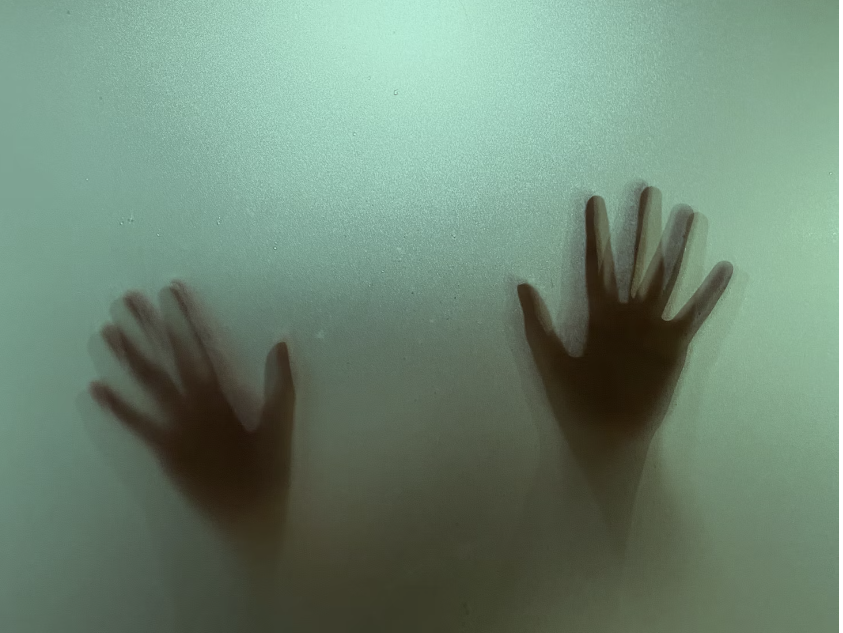

Sleep paralysis is a deeply researched phenomenon in which, during sleep, you are unconscious and yet unable to move (prompting the apt name). Now, you can still curl your toes, flex your hands, or twist and turn, but you can’t actually get out of your bed and say, clean your house (provided you don’t have night terrors or some other conflicting sleep disorder). But how does sleep paralysis occur? Why can’t we just do our chores when we are dreaming, or rather dreading, them the next day?

Our brain is considered to be one of the most complex objects there is. From being able to have half of it removed and still function just about perfectly (in another phenomenon referred to as plasticity, or the brain’s ability to repair itself), to being able to not feel pain and yet regulate pain for all the other parts of the body, it’s a pretty unique and powerful organ. Millions of neurons and hundreds of parts within it work to make it function as it does, all without making us sweat even a little. But there are three particular things that explain sleep paralysis: the brain stem, the motor cortex, and movement signals.

The motor cortex is responsible for initiating your movements. Whether it’d be raising your arms to stretch, climbing a step with your legs, or even scrolling on your phone, you can thank your motor cortex. In all of these actions, the motor cortex sends movement signals to your brain in order to actually cause you to, well, move. During sleep, although you are not conscious, your brain still is active (as it doesn’t ever ‘shut off’). The body acknowledges this and programs your brain stem to block all movement signals from the motor cortex in an effort to protect you by preventing you from wandering off and, say, doing some chores.

You might be wondering why you can still curl your toes, toss and turn, or even move away from something unpleasurable. After all, the motor cortex is responsible for movement, no? Well, that’s true to an extent: it’s responsible for all voluntary movement, that is. Remember your last doctor’s appointment where they used the tiny rubber hammer to test your knee’s reflexes? That wasn’t voluntary, so instead of going up to the brain, it is only sent to the spinal cord, which the brain stem does not block movement signals from. As such, all reflexes (and certain small movements) are permissible by the brain because, well, they don’t actually go through it.

The brain is an intricate thing. It’s responsible for every single facet of your life, and yet does its job so seamlessly that we hardly even think about it. It even protects us at night when we are sleeping. What else can the brain do that we haven’t discovered? What else does the brain do that we marvel about?

Sources

- https://www.sleepfoundation.org/parasomnias/sleep-paralysis

- https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/21974-sleep-paralysis

- https://sleepdoctor.com/parasomnias/sleep-paralysis/